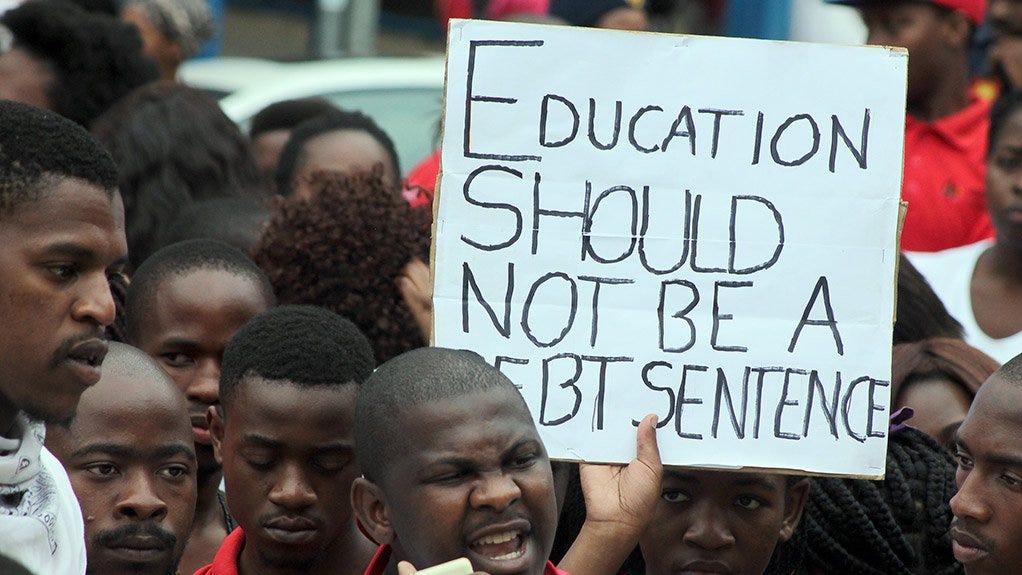

A Decade After #FeesMustFall, Students Are Still Fighting for Education

Rising costs, policy failures, and housing shortages continue to shut students out of higher education in South Africa.

The recent protest at the University of Cape Town over education made me ask how the world sees tertiary education. Is it believed to be a privilege or a right, and how should that frame the discourse here in South Africa?

I came across a social media post stating, “Tertiary education should be a human right.” I thought this was an interesting statement. However, nothing in the Constitution of South Africa references that tertiary education ought to be a right.

The Constitution states, “section 29(1) obliges government to make education available and accessible to everyone. Section 29(1)(a) in particular entitles everyone to a basic education.” This creates a great deal of controversy because accessibility does not necessarily mean free; secondly, it does not obligate any party to ensure students remain educated.

We are commemorating a decade since #FeesMustFall in South Africa, and we are witnessing a similar situation. Once again, the economic disparities in South Africa present themselves most evidently to students who are unable to access housing.

NSFAS, the National Student Financial Aid Scheme, being run by the government, fails at ensuring accessibility after policy changes made in 2023 that capped housing funding, “The NSFAS accommodation cap, introduced in 2023 and continuing this year, limits annual accommodation funding to R50 000 per student.”. Students cannot access their accommodation or even transcripts due to debts owed to the school. Suddenly, failures of government become more apparent.

In many ways, the onus is always on students to resolve issues they have, most of the time, not created. Students are left with the same problem on a year-to-year basis. It is evident that a newly formed government needs to not only deliver on its promises but also deliver on its duty to create a legitimate tertiary education environment as an access point.

Particularly, CPUT and the University of Cape Town are concerned that they are unable to survive on a R50 000 a year housing cap with an increased rate of living as the city is dominated by tourists and expats. In many ways, the government and all those involved need to step in and take action and deliver the students some relief or solution to the ongoing problem.

Many students are already overcoming structural barriers and competitive selection pools to access universities in hopes of having a chance at social mobility. We must find ways to empower students and not limit them.

In some ways, every student who is denied a degree and is unable to reach a concession with the school is denied an opportunity and a completely different world. Their hard work is left unnoticed, and their opportunities are limited.

In South Africa, we already do not have enough universities, and hundreds of thousands of students are rejected from many of these institutions. We can not allow the ones who make it into these universities to share the same fate after taking on this journey.

There is widespread recognition that these institutions have operating costs and overheads that need to be covered. But we ought to remember that their primary aim is to teach, innovate, and advance critical thinking and discussion.

In many ways, we hope that universities will be the place to liberate and enlighten the minds of tomorrow. However, they currently enrage and invoke disappointment without the light of tomorrow.