Thirty Years On: Revisiting the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Impact

Evaluating Reconciliation, Justice, and Governance in Post-Apartheid South Africa

The outcome of the Truth and Reconciliation Council (TRC) has never been tested as it needs to be in South Africa at the moment. With conversations around the ANC and DA co-governing, questions arise about whether or not South Africa will be able to establish itself outside of race politics, which is fundamental to the progress and development of the country.

The TRC was meant to address the injustices of the past and ensure victims were informed about the actions perpetrators committed during Apartheid. Additionally, there was an incentive for perpetrators to come forward in hopes of receiving amnesty from the South African government. Major queries arose regarding the question of justice and whether or not it was felt by the people that ‘justice’ truly had been served, as many Apartheid perpetrators walked free. Though only 1,167 out of 7,112 received amnesty, there was a failure to implement punishable actions on the other side. Additionally, there was a lack of willingness from the Apartheid state president to appear as a whole. Did we truly reconcile as a country?

During the TRC process, many debates questioned whether or not the South African public was willing to move forward and form a nation under one rainbow. Yet, that rainbow is already facing its rainy day. For instance, F.W. de Klerk proclaimed the TRC was a “witch hunt,” and the Winnie Mandela cases around Stompie Seipei showed a failure of the TRC to deliver justice. Powerful leaders who committed human rights abuses refused to show remorse for their actions. Consequently, there was a growing feeling among white minorities that this was a targeted attack and a means of balancing the scales. Conversely, many in the black majority felt that the government failed to hold perpetrators accountable. However, at the end of seven years, neither of these issues were fully addressed, and there was also a failure to discuss economic and social policy to achieve true reconciliation.

So, at the end of the seven-year process, which began in 1995 and ended in 2002, the illusion that South Africans can cohabit and coexist peacefully was created due to the constant media attention the TRC held both locally and internationally. Now, 30 years later, it seems the TRC failed in more ways than one.

Thirty years later, South Africa speculates about which coalition government is likely to take place. Many ANC members, both within the political party and among supporters, have expressed that a deal with the DA would be a betrayal of their principle to govern independently of white rule. This raises the question of whether or not the TRC was meant to create a world where governance could occur without race being a factor. Alternatively, the lack of economic progress felt by many South Africans due to the failures of the ANC has left many feeling uncertain about the DA's desire to protect the common man. The DA’s advocacy against a minimum wage and BEE—both policies that affect the majority of the country—has led to fears that it could lead to direct trade-offs of the most vulnerable.

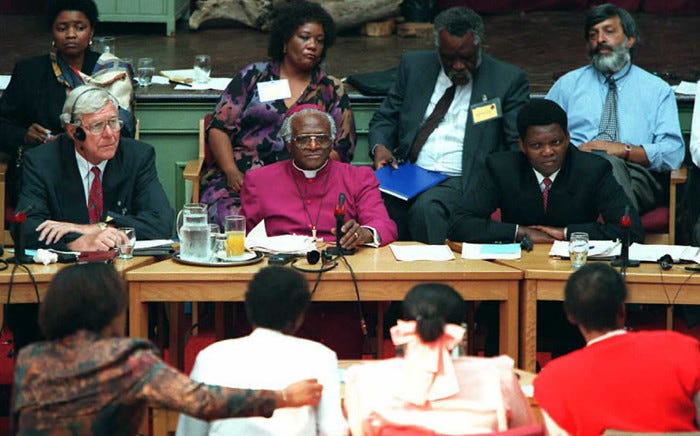

Desmond Tutu recognized at the end of the TRC process that there was a necessity to continue the process and allow space for conversations about victims and their experiences to continue to be shared with the South African public. However, due to financial constraints, there was a necessity to shut it down. Additionally, the TRC recognized that families had been impacted financially and included a reparation pillar as part of the commission. Due to a failure to pay out individuals and the inability to quantify pain, the government recognized the need to put money in the hands of those who have been economically excluded, but there was a failure to create a long-term system to address the inequalities faced by many South Africans, which were only exacerbated as the state failed to deliver infrastructure.

Furthermore, the failure to establish and continue interracial relationships in all aspects of society meant that there were different interpretations of the outcomes of the TRC. For some, the TRC was successful and allowed us to coexist; for others, it was a witch hunt. For many, it failed to deliver justice, but for others, it set South Africa on the right path. Now, 30 years later, we are unable to co-govern independent of race because of the false belief that we are an “integrated” country. However, many South Africans are unwilling to come to the table to protect the stability of the nation. But that is not by their own doing; it is a failure of the parties to adapt to the needs of most South Africans.

In evaluating the TRC, it is important to recognize its benefit in progressing South Africa as a nation and building a collective identity we could all buy into. It was vital, but with the failure to economically and socially progress people, its impact has diminished significantly. So, was it the failure of the TRC or the failure of the ANC?